It was a war no one asked for, to kick off a plan everyone rejected and the first battle was an absolute disaster for every British soldier involved. It all started when British Colonial Secretary Henry Herbert, Earl of Carnarvon decided he wanted to implement a confederation system in southern Africa, similar to the system he created for bringing the Canadian colonies together in 1867. After all, it worked for Canada, why wouldn’t it work in Africa?

Because Zulus aren’t Canadian. Or British. At all.

There was just one problem: Britain didn’t actually control all of southern Africa and the areas it did control didn’t want to be confederated into one big colony. They even told Carnarvon that such an arrangement could disenfranchise the colony’s black citizens (spoiler alert: it did). Despite the colony neither wanting nor needing the confederation, and the relative peace between the neighbors there, Carnarvon sent Sir Henry Bartle Frere to South Africa to implement it anyway.

In order to get started, they first needed to actually conquer what they didn’t control: the Zulu Kingdom and the Boers of the South African Republic. To kick off the war with the Zulus, Frere sent an ultimatum to Zulu King Cetshwayo. It was an order to effectively disband his military, and one he knew Cetshwayo would reject. When the king ignored it (as planned), the British used this rejection as a casus belli to invade Zululand.

General Frederic Augustus Thesiger, Lord Chelmsford was picked to lead the British forces against the Zulus. On paper, he was eveything you might want: a veteran of the Crimean War, the 1857 Indian Rebellion and Xhosa Wars. All that experience, however, led to more than a little hubris. His experience against the Xhosa Kingdom left him unimpressed with the native troops of Africa and led him to make some of the dumbest possible mistakes in his war with the Zulus.

Zulus, as it turns out, were very different from the Xhosa.

On January 11, 1879, Chelmsford divided his 7,800 British regulars, Boers and native troops into three columns, all headed toward the Zulu capital of Ulundi. In their rush to implement the colonial plan, the troops left right away, meaning they were not only about to divide their forces, they were about to march into war during the rainy season. Less than a week later, 24,000 Zulu warriors left Ulundi to meet them.

The Zulu were able to move an average of 10 miles per day, compared to one miles for the British. The British also had no idea where the main Zulu force was. Chelmsford was seriously underestimating his enemy. When they made camp at Isandlwana on January 20, the army made no entrenchments, failed to circle their wagons and basically failed to create any kind of fortifications. Chelmsford believed superior weapons and European training could overcome anything an African force threw at him. He was, of course, wrong.

What the British did do was send out scouts who encountered a force of Zulu skirmishers, which he believed was part of the main Zulu army. He then divided his forces even further, leaving 1,300 men (only 600 of which were regulars) to guard the camp, under the command of an officer with no combat command experience. While Chelmsford was gone, the Zulus had moved around his entire detachment and were just seven miles from the camp at Isandlwana.

Just take a load off, guys. I’m sure the Zulus aren’t coming. Probably.

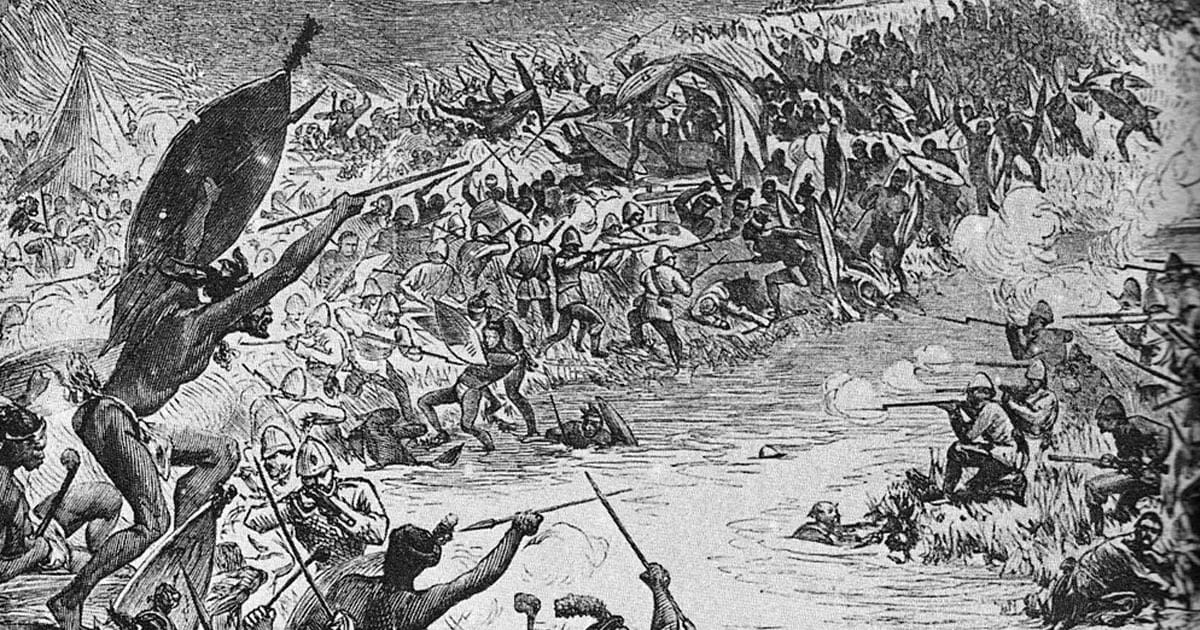

Around 11 a.m. on January 22, British cavalry scouts found the entire force of 20,000 Zulus quietly hiding in a valley. When they were discovered, they quickly moved into battle formations, forcing the scouts to fight their way back to the camp. The 1,837 defenders of Isandlwana quickly found themselves outnumbered, with 20,000 enemy warriors moving to outflank or encircle them.

The British fought until they ran out of ammunition, then fought on with their rifles and bayonets. British regulars were killed to the last man. The African native troops who fought alongside them were executed as traitors by the Zulus. Some 1,300 of the British died at Isandlwana and the rest were allowed to escape. The British were forced to retreat from Zululand entirely after their supplies, ammunition and draught animals were captured.

Reactions to the defeat resounded throughout the British Empire. Instead of rethinking the entire scheme, support for the conquest of Zululand only increased with the British defeat. Desperate to show the empire wasn’t weak, another force was shipped to South Africa for another invasion. Sir Henry Bartle Frere was recalled to London after the defeat at Isandlwana and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli’s conservative government lost the next elections.

It would also lead to a banger of a Michael Caine movie some 100 years later.

Chelmsford was supposed to be relieved of command, but stayed on by blaming the failure to build defenses in the camp on another officer, Col. Anthony Durnford, who had only arrived at the camp on the day of the battle. After the fall of Ulundi in July 1879, however, Chelmsford would never receive another field command.

As for the plan to unite the colonies under one confederation, the Boers of the South African Republic weren’t going down without a fight, either. The Boers would beat the British in the 1880-81 Boer War and would remain an independent state until 1902, when the British finally annexed the country after the Second Boer War, which inflicted some 99,000 casualties on British troops.